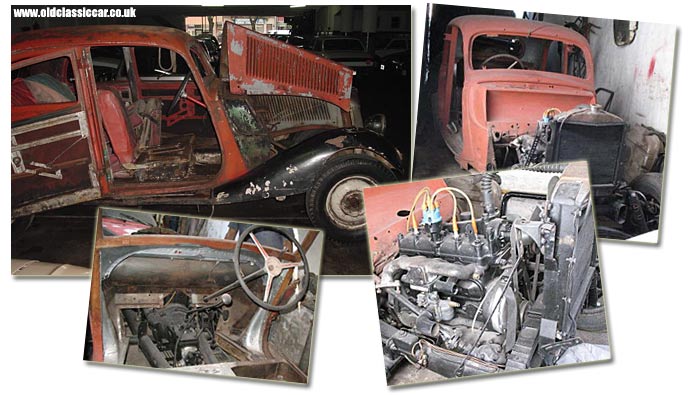

Mercedes Benz 170V restoration project.

Gustavo Bondoni contacted me in May 2010, with the story of a pre-war Mercedes Benz 170V that he's been restoring. To say things have been very eventful would be something of an understatement. At the time of writing this, he is away working in Mexico, the car remaining in Argentina where the work on it continues. Hopefully later instalments in this epic tale will describe how the Mercedes returns to the road. So, for the time being, here is the restoration story so far, in Gustavo's own words...

|

|

Curse of the Car.

"A lot of people much smarter than I am told me it was a dumb idea. Almost everything written by automotive journalists agreed. Nevertheless, I went ahead and did it anyway. That is to say, I am doing it anyway.

|

|

And what, you might ask yourself, was the prevailing wisdom that I so blithely ignored? It was this: if you’re going to do a ground-up restoration of a barn-find, it’s only worth doing if the car in question is a matching-numbers, ex-Le Mans Ferrari 250 GTO, Shelby Daytona Coupe or, maybe, Achille Varzi’s old Alfa Romeo P3.

|

|

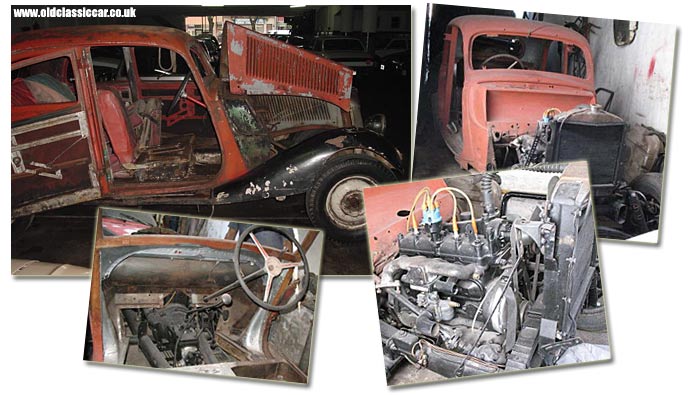

Serious projects involving, say, an early seventies mini, or, even worse, a late thirties' Mercedes 170V with rotten semi-structural wood frame and the engine on the front seat would be studiously avoided by the kind of people who generate automotive wisdom. The reason that a ratty old 170V, not normally the first car one would think of when evaluating possible restoration candidates, crops up in the conversation is that it’s precisely what I went out and bought.

|

|

Why, exactly? Well, the usual reasons. The money burning a hole in my pocket probably contributed, as did the fact that the car in question is a Mercedes, which is always a good reason, even when dealing with the less-glamorous models. But I think that what really tipped the balance (as I believe it does for all inexperienced old-car enthusiasts) is that the car was available now, and that it was worth about four hundred dollars.

Think about it: your own pre-war Merc for only $400. Some assembly, admittedly, was required; the car had seen better days. But it was nothing a well-adjusted person with a decent shrink couldn’t take relatively calmly, if he or she were totally clueless.

|

|

Cue me. The engine, as I have mentioned, was in the front seat. Or, I should say, the block was in the front seat while the rest of the engine sat in a box in the back seat, although this was not immediately apparent as the box was partially obscured by the gearbox and the radiator piled on top of it.

Serving as counterpoint to the stuff piled inside the car was the once semi-load-bearing wooden frame. The wood, rotten as it was, could only serve as the pattern for a complete replacement.

|

|

Even worse were the seats. They weren’t even good enough for patterns, and someone along the way had decided that orange vinyl was just right as upholstery. I kept them, but only because I was too chicken to throw them out.

|

|

On the other hand, the sheet metal was in surprisingly good shape. It turns out that Mercedes-Benz wasn’t fooling around when they built these things. Or maybe they raided the warehouse where the Panzer armor was stored (1939, remember). It was solidly built, and still solid after sixty-odd years, the last fifteen of which had been spent uncovered, in an oft-flooded field.

|

|

So I bought it from an old man with a tremendous store of M-B parts in a shed, took it, on a truck, to the garage where I kept my daily driver and left it there while I found a restorer. I, of course, am unable to change a sparkplug and am even severely challenged by tire irons.

|

|

So where do you look for a restorer? Here’s a hint, which is free to you (it was expensive to learn in my case). Enthusiasm is not a good substitute for knowing what you’re doing. In my case, the eighteen-year-old brother of one of my friends, let’s call him Pablo to protect the innocent, decided it would be a great idea to give the restoration a shot. He was, after all, tinkering with his car and repairing, in parallel, an Argentine coupe from the sixties. He would repair the engine and chassis for a small amount of money.

|

|

In principle it looked like a win-win setup. He had a large garage at his girlfriend’s house, where he could work unimpeded. The girlfriend herself, though a little older than him, seemed unlikely to cause much trouble – a pleasant, tranquil girl with a five year-old daughter and a dog.

And at first, everything went perfectly. The Mercedes' body was quickly removed from the chassis, the engine was stripped, a great used crankshaft sourced to replace the original (sadly broken in half), and a lot of stuff sanded and painted. The gearbox was quickly up and running, and the completely stripped chassis rails straightened to repair crash damage and also painted. All of this took place in a couple of months.

We also got the body to the carpenter’s shop, after much lifting, loading onto flatbeds, unloading from flatbeds and cursing.

And then the young man’s inexperience came into play.

|

|

A Mercedes-Benz 170V engine is a 1700 cc four-cylinder sidevalve. It is not a complicated piece of equipment, even by laymen’s standards, having been designed (successfully) to be a rugged, long-lasting machine. It does, however, contain technology that is simply no longer used. The most notable is the fact that the con rods use white-metal coating of a type which only specialists carry out. My young mechanic’s attempts to get shell bearings for the rods were met, in the best of cases, by bemused expressions. In the worst cases, they sold him useless parts.

Eventually, the engine was shipped off to get rectified by a third party. And, at about this time, all progress ground to a halt. The car had been turned into three major components – body (no work had started on the wood due to the carpenter being busy with several other projects), chassis (in bits) and engine (in more bits and in a different location), and was now just lying around doing nothing.

|

|

And then I learned the second lesson. Never pay for anything up front.

|

|

|

My phone calls went unanswered, which, in turn caused my temper to flare at the very thought of the mechanic’s existence. At the same time, my enthusiasm for the project began to fade, driven down by a sense of the woeful futility of the continued waste of money and time that it implied.

Finally, a few months later, I got a call from the mechanic. He’d broken up with the girlfriend who owned the house, and had been operated on for thyroid cancer – successfully, fortunately – and was disinclined to continue working on the car. And, by the way, the girlfriend needed the garage back, so could I kindly remove the rusty hulk?

|

|

It was the first inkling that coming into contact with this particular restoration was not necessarily a healthy proposition, but I put the breakup down to the guy’s immaturity, and the health scare to an unfortunate coincidence. I would, however, learn. The following few days were a frantic mess, as can well be imagined. I needed to find a new mechanic now, as well as drag the wheel-less chassis to the new premises. A couple of people told me that they wouldn’t willingly take on a project quite that major and long-term, while other options were just silly.

|

|

Finally, the man who’d sold me the car in the first place came up trumps, or so it seemed. He had a longtime acquaintance, a fellow in his seventies, who’d been a mechanic his whole life, having learned at his father’s knee, and knew M-B 170 Vs inside-out.

|

|

I met the man, chatted old Mercedes lore for a while, was impressed by his knowledge, and promptly made agreed to let him work on the vehicle. The only downside was that he lived in a trailer on an unbuilt-up property in an area that was best not braved at night. But I decided that it was actually better to have a good mechanic than to be one of those people who avoids dangerous suburban areas. Then I got some friends from work to help me drag it out of the ex-girlfriend’s garage. Fortunately, this long-suffering soul did let the car remain longer than she’d originally planned, which probably saved the whole project.

|

|

I left the car with the new mechanic, and the stalled project began to pick up steam. Earlier errors, caused by the younger man’s inexperience, were identified and corrected. Wheel bearings that were installed incorrectly, which would have caused the wheel to go one way and the car to go another (presumably over the nearest high cliff) were fixed. Parts lost in the move were inventoried, and the engine was removed from the shop where it had been languishing, accompanied by much squinting and head-scratching, and taken to a completely new and different shop, which reputedly knew what it was doing.

|

|

The saddest part of this stage in the process was the inventory. At least a couple of expensive engine bits had gone off for parts unknown, and so had the shock absorbers (fortunately, we’d settled on using telescopic shocks in place of the enormously expensive originals, which reduced the severity of the loss).

|

|

At this point, we need to reintroduce one of the main characters of the story: The man who’d originally sold the car to me. As I mentioned, he also had an enormous stock of Mercedes-Benz parts in a large shed at the side of his house. At first, I was a bit resentful and suspicious of his motives, believing that he’d only sold me the car itself in order to then foist all his excess stock of bits and pieces off on me.

|

|

In the initial stages of the project, I ignored his offers to find me spares in, I must admit, a somewhat huffy way. After all, when things are going well, it’s easy to act superior. When the hitches began to arrive, one after the other, I began to listen to the old fellow, and we gradually became good friends. He did eventually sell me some parts, but, much more importantly, became an invaluable source of information and advice. The new mechanic was actually a man he recommended, and so was the new engine shop.

|

|

This activity was followed by a flurry of production. The suspensions and steering box were soon mounted, the brakes refurbished, four decent tires obtained, and the dragged chassis became a rolling chassis for the first time since the very beginning of the project. It was a beautiful moment.

The engine, also, returned from the shop, fully rectified and mounted. A small, if expected snag was hit when we discovered that it wouldn’t turn over, being jammed solid, but that was immediately remedied at no extra cost. The engine mounts – one of the pieces that had gone AWOL during the move – were sourced and restored, and the motor placed on the chassis, connected to the driveshaft and the beautifully reworked differential.

|

|

For six months, everything seemed to be going smoothly. Expensively, and sometimes with great difficulty in obtaining parts, but smoothly.

I was even enthusiastic enough with the progress that I badgered the carpenter into starting work on the wood, feeling that the chassis would be ready to receive the bodywork for an initial fitting in short order. After that, it would have to be removed again to repair rust damage, but that would be relatively straightforward. Confidence was high.

|

|

Then, one day, about six months after the new mechanic began work on the car, I was sitting at my desk in the office, relatively at peace with the world, when the phone rang.

|

|

“Hello,” a woman’s voice said, “Is this Gustavo?”

|

|

I admitted it, slightly unsettled by the broken quality of the voice. “Who is this?” I asked. The voice on the other end of the line explained that she was my mechanic’s wife. I asked if anything wrong, already sensing that something, something serious, was.

|

|

“Only the worst possible thing in the world,” she replied, before being overcome by tears.

|

|

The mechanic, though elderly, had shown no signs of declining health. He was a tall man, a big man, who I would have pegged to outlive me, if I’d been asked. But he hadn’t. His heart had let go suddenly one afternoon.

|

|

I was shocked and saddened by the news. The guy had been friendly and outgoing, despite having led a hard life full of bitter disappointment – a typical fate for people in Argentina – and I’d grown to like him quite a bit. It took a while for the news to sink in. But once it did, I realized that it was a serious, possibly killing, blow to the project. His old yard and shed were in a really unsafe part of the suburbs, and it wouldn’t be long before bits started disappearing from the now unguarded car. I needed a new mechanic very, very quickly.

|

|

Once more, my old friend Juan Carlos, the man who’d originally sold me the car, came to my rescue. He had another acquaintance, a younger, healthier man this time, who had a workshop nearby, and who might be persuaded to take on the project. I quickly called and made the arrangements, and all was set. The car was soon transferred to the new premises.

|

|

To tell the truth, I felt a little guilty about putting yet another life at risk with this project. It had already had one breakup, one cancer scare and one death associated with it. And yet, not being superstitious, I went ahead anyway.

|

|

Sadly, yet another complication, a completely unexpected one this time, cropped up. The mechanic’s widow, heretofore a friendly person who’d been supportive and pleasant, showed a darker side.

|

|

First, there was the episode in which she claimed that I owed the dead mechanic, and therefore her, a considerable sum of money. This, I conceded, was not an impossibility, so we sat down to calculate what had been done since the last infusion of cash. Mainly in an attempt to give the widow a hand, and not because of any actual evidence, I accepted a smaller amount as due. It wouldn’t, I reasoned, hurt me, and it might conceivably help her. To this point, I was slightly miffed at the situation but thought it was probably a misunderstanding.

|

|

That misconception lasted almost no time at all. When the time came to remove the car from the lot, we discovered that some pieces which I had purchased over the past couple of years had gone mysteriously missing. We assumed that vandals had gotten into the unsecure area and taken, in their ignorance, whatever was loose and easily gotten at. Nothing of real value was gone, but it was still irritating.

|

|

Sadly, the truth was more depressing. I learned through the classic car grapevine, that the evil old lady had decided to open bidding on the parts of my car in her possession, and anyone coming up with cash could pick and choose. She would then use the “thieves walked in and took the bits” defense, and nobody would be the wiser. It was only fortune that kept the more valuable parts from “being stolen”.

|

|

The only good part about this is that I was able to tell her that she would be receiving not one cent of the money we’d agreed on. The subsequent screeching – both from her and a daughter-in-law who I assume was an accomplice – caused me enormous satisfaction, and not one shred of guilt. Our evidence had been iron-clad.

|

|

So we returned to work on the vehicle, admittedly suffering all the misgivings associated with the fact that some supernatural power was truly set against it ever being complete. I often wonder if, when the time comes, I will be brave enough to drive it. It does, after all, come equipped with a steering column that resembles nothing so much as one of those Spartan spears from the movie “The 300”. No collapsible safety devices for the pre-war German. They were real men, those Teutons.

|

|

Progress, like an avalanche, resumed. I thought it was amazingly strange that every time I changed from one mechanic to the next, the project got jumpstarted. Even people with no connection whatsoever to the mechanic seemed to get in on the act. It was just as the new mechanic began to get many of the car’s systems going that I got a call from the carpenter saying that the wood frame for the body was complete, and could I go down there and take a look.

|

|

I went, and found that he’d done a beautiful job. The woodwork was to marine carpentry standards which, hopefully, means that it will outlast everything else. You could tell it was high quality just by looking at it, even if, like me, you were an uneducated layman.

|

|

I was energized by this development, and by the fact that, after more than thirty years of inaction, the engine was soon running. It, like the brakes, the grease nipples and various other subassemblies were mounted on the chassis and gleaming. The sound of the motor after all these years felt to me like a bugle at dusk sounding victory on the field.

|

|

This wasn’t all. The Mercedes' bodywork – sans doors and still needing rust correction – was retrieved from the carpenter’s shop and reunited with the chassis. This was temporary, but, for the first time in about four years the car looked like… a car! Enthusiasm was at an all time high, the light at the end of the tunnel could be glimpsed and I was hoping for a quick resolution.

|

|

Then, of course, the curse struck my newest mechanic.

|

|

As I’d mentioned before, his workshop was stationed near the previous mechanic’s place. Not the safest of areas. So it came as little surprise to me when persons unknown broke into it and stole all his tools. The car came out of it unscathed, but all progress came to a halt as he re-equipped. He wasn’t a wealthy man, and tools were expensive, and this took some time. We spent most of this time discussing what we’d do next.

|

|

It turned out that the guy had confidence in his welding. He’d already proven himself to be a craftsman of the highest order on the mechanical side, so I immediately agreed to let him have a go at the bodywork. This proved to be an inspired decision, as it transpired that he was a perfectionist artist type who was also unbelievably inexpensive.

|

|

Work slowly began once more. Welding occurred, and the floor and body slowly went from rusty to solid. New metal was shaped, placed and welded.

And then, after nearly five years of restoration, the curse finally looked around, realized the error of its previous ways, and got around to hitting me.

The whole expensive restoration to date had been financed out of my own pocket. It hadn’t been done for profit, just out of the deep-seated desire to see a magnificent vehicle on the road once again. I love old cars and I could afford it. Until, of course the day I lost my job. That created a bit of an issue.

|

|

I spent most of the following year looking for a new employment, but, when I finally found it, it was seven thousand miles from the car, in Mexico City, which is where I’m currently writing from. I sometimes visit Argentina and take the mechanic some money, and work progresses slowly.

|

|

Nevertheless, I can’t help but feel that the curse, having gotten me out of the way is planning some major disaster. A fire, an earthquake, a meteor strike. Something as nasty as it is unlikely. That, not any job-related stress or existential angst is what keeps me up at night.

|

|

Oh, and old Juan Carlos, the man who’d originally sold me the car hasn’t shown any signs of life for the past six months, either…"

|

|

Thanks for the story so far Gustavo - hopefully the remainder of this Mercedes Benz' restoration will go a little more smoothly than it has done to date! I look forward to future updates :-)

|

|

Your Classic Cars section at oldclassiccar

|

|

A number of photos featuring classic Mercedes cars feature elsewhere on the site, for instance this page which will feature period shots of the 170 range.

|